Dear Readers,

In this blog we are going to learn about, Byte order, or endianness, is a fundamental issue in computing where machines interpret and store multi-byte data, such as integers, differently. This text explores the challenges posed by byte order discrepancies, presenting two key solutions: establishing a common data format, known as network order, and using byte order marks (BOMs) to indicate data endianness. By delving into these strategies, this discussion sheds light on how computers manage byte order issues when exchanging data, offering insights into the complexities of data interpretation and storage across diverse computing platforms.

Problems with byte order are frustrating, and I want to spare you the grief I experienced. Here’s the key:

- Problem: Computers speak different languages, like people. Some write data “left-to-right” and others “right-to-left”.

- A machine can read its own data just fine – problems happen when one computer stores data and a different type tries to read it.

Solutions

- Agree to a common format (i.e., all network traffic follows a single format), or

- Always include a header that describes the format of the data. If the header appears backwards, it means data was stored in the other format and needs to be converted.

Numbers vs. Data

The most important concept is to recognize the difference between a number and the data that represents it.

A number is an abstract concept, such as a count of something. You have ten fingers. The idea of “ten” doesn’t change, no matter what representation you use: ten, 10, diez (Spanish), ju (Japanese), 1010 (binary), X (Roman numeral)… these representations all point to the same concept of “ten”.

Contrast this with data. Data is a physical concept, a raw sequence of bits and bytes stored on a computer. Data has no inherent meaning and must be interpreted by whoever is reading it.

Data is like human writing, which is simply marks on paper. There is no inherent meaning in these marks. If we see a line and a circle (like this: |O) we may interpret it to mean “ten”.

But we assumed the marks referred to a number. They could have been the letters “IO”, a moon of Jupiter. Or perhaps the Greek goddess. Or maybe an abbreviation for Input/Output. Or someone’s initials. Or the number 2 in binary (“10”). The list of possibilities goes on.

The point is that a single piece of data (|O) can be interpreted in many ways, and the meaning is unclear until someone clarifies the intent of the author.

Computers face the same problem. They store data, not abstract concepts, and do so using a sequence of 1’s and 0’s. Later, they read back the 1’s and 0’s and try to recreate the abstract concept from the raw data. Depending on the assumptions made, the 1’s and 0’s can mean very different things.

Why does this problem happen? Well, there’s no rule that all computers must use the same language, just like there’s no rule all humans need to. Each type of computer is internally consistent (it can read back its own data), but there are no guarantees about how another type of computer will interpret the data it created.

Basic concepts

- Data (bits and bytes, or marks on paper) is meaningless; it must be interpreted to create an abstract concept, like a number.

- Like humans, computers have different ways to store the same abstract concept. (i.e., we have many ways to say “ten”: ten, 10, diez, etc.)

Storing Numbers as Data

Thankfully, most computers agree on a few basic data formats (this was not always the case). This gives us a common starting point which makes our lives a bit easier:

- A bit has two values (on or off, 1 or 0)

- A byte is a sequence of 8 bits

- The “leftmost” bit in a byte is the biggest. So, the binary sequence 00001001 is the decimal number 9. 00001001 = (23 + 20 = 8 + 1 = 9).

- Bits are numbered from right-to-left. Bit 0 is the rightmost and the smallest; bit 7 is leftmost and largest.

We can use these basic agreements as a building block to exchange data. If we store and read data one byte at a time, it will work on any computer. The concept of a byte is the same on all machines, and the idea of which byte is first, second, third (Byte 0, Byte 1, Byte 2…) is the same on all machines.

If computers agree on the order of every byte, what’s the problem?

Well, this is fine for single-byte data, like ASCII text. However, a lot of data needs to be stored using multiple bytes, like integers or floating-point numbers. And there is no agreement on how these sequences should be stored.

Byte Example

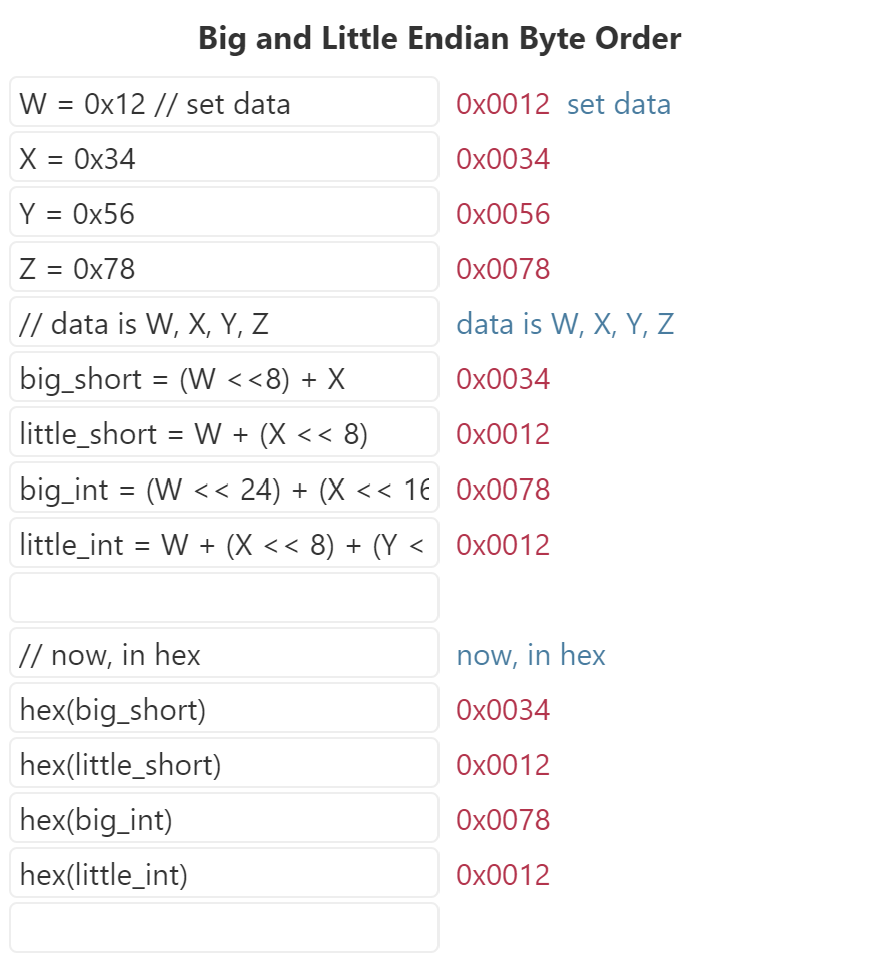

Consider a sequence of 4 bytes, named W X Y and Z – I avoided naming them A B C D because they are hex digits, which would be confusing. So, each byte has a value and is made up of 8 bits.

Byte Name: W X Y Z Location: 0 1 2 3 Value (hex): 0x12 0x34 0x56 0x78

For example, W is an entire byte, 0x12 in hex or 00010010 in binary. If W were to be interpreted as a number, it would be “18” in decimal (by the way, there’s nothing saying we have to interpret it as a number – it could be an ASCII character or something else entirely).

With me so far? We have 4 bytes, W X Y and Z, each with a different value.

Understanding Pointers

Pointers are a key part of programming, especially the C programming language. A pointer is a number that references a memory location. It is up to us (the programmer) to interpret the data at that location.

In C, when you cast a pointer to certain type (such as a char * or int *), it tells the computer how to interpret the data at that location. For example, let’s declare

void *p = 0; // p is a pointer to an unknown data type

// p is a NULL pointer -- do not dereference

char *c; // c is a pointer to a char, usually a single byte

Note that we can’t get the data from p because we don’t know its type. p could be pointing at a single number, a letter, the start of a string, your horoscope, an image — we just don’t know how many bytes to read, or how to interpret what’s there.

Now, suppose we write

c = (char *)p;

Ah — now this statement tells the computer to point to the same place as p, and interpret the data as a single character (char is typically a single byte, use uint8_t if not true on your machine). In this case, c would point to memory location 0, or byte W. If we printed c, we’d get the value in W, which is hex 0x12 (remember that W is a whole byte).

This example does not depend on the type of computer we have — again, all computers agree on what a single byte is (in the past this was not the case).

The example is helpful, even though it is the same on all computers — if we have a pointer to a single byte (char *, a single byte), we can walk through memory, reading off a byte at a time. We can examine any memory location and the endian-ness of a computer won’t matter — every computer will give back the same information.

So, What’s The Problem?

Problems happen when computers try to read multiple bytes. Some data types contain multiple bytes, like long integers or floating-point numbers. A single byte has only 256 values, so can store 0 – 255.

Now problems start – when you read multi-byte data, where does the biggest byte appear?

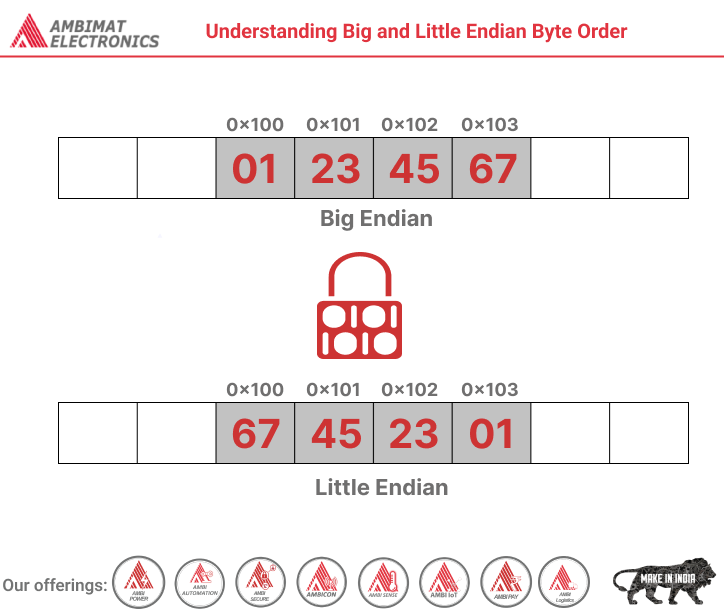

- Big endian machine: Stores data big-end first. When looking at multiple bytes, the first byte (lowest address) is the biggest.

- Little endian machine: Stores data little-end first. When looking at multiple bytes, the first byte is smallest.

The naming makes sense, eh? Big-endian thinks the big-end is first. (By the way, the big-endian / little-endian naming comes from Gulliver’s Travels, where the Lilliputans argue over whether to break eggs on the little-end or big-end. Sometimes computer debates are just as meaningful :-))

Again, endian-ness does not matter if you have a single byte. If you have one byte, it’s the only data you read so there’s only one way to interpret it (again, because computers agree on what a byte is).

Now suppose we have our 4 bytes (W X Y Z) stored the same way on a big-and little-endian machine. That is, memory location 0 is W on both machines, memory location 1 is X, etc.

We can create this arrangement by remembering that bytes are machine-independent. We can walk memory, one byte at a time, and set the values we need. This will work on any machine:

c = 0; // point to location 0 (won't work on a real machine!) *c = 0x12; // Set W's value c = 1; // point to location 1 *c = 0x34; // Set X's value ... // repeat for Y and Z; details left to reader

This code will work on any machine, and we have both set up with bytes W, X, Y and Z in locations 0, 1, 2 and 3.

Interpreting Data

Now let’s do an example with multi-byte data (finally!). Quick review: a “short int” is a 2-byte (16-bit) number, which can range from 0 – 65535 (if unsigned). Let’s use it in an example:

short *s; // pointer to a short int (2 bytes) s = 0; // point to location 0; *s is the value

So, s is a pointer to a short, and is now looking at byte location 0 (which has W). What happens when we read the value at s?

- Big endian machine: I think a short is two bytes, so I’ll read them off: location s is address 0 (W, or 0x12) and location s + 1 is address 1 (X, or 0x34). Since the first byte is biggest (I’m big-endian!), the number must be 256 * byte 0 + byte 1, or 256*W + X, or 0x1234. I multiplied the first byte by 256 (2^8) because I needed to shift it over 8 bits.

- Little endian machine: I don’t know what Mr. Big Endian is smoking. Yeah, I agree a short is 2 bytes, and I’ll read them off just like him: location s is 0x12, and location s + 1 is 0x34. But in my world, the first byte is the littlest! The value of the short is byte 0 + 256 * byte 1, or 256*X + W, or 0x3412.

Keep in mind that both machines start from location s and read memory going upwards. There is no confusion about what location 0 and location 1 mean. There is no confusion that a short is 2 bytes.

But do you see the problem? The big-endian machine thinks s = 0x1234 and the little-endian machine thinks s = 0x3412. The same exact data gives two different numbers. Probably not a good thing.

Yet another example

Let’s do another example with 4-byte integer for “fun”:

int *i; // pointer to an int (4 bytes on 32-bit machine) i = 0; // points to location zero, so *i is the value there

Again we ask: what is the value at i?

- Big endian machine: An int is 4 bytes, and the first is the largest. I read 4 bytes (W X Y Z) and W is the largest. The number is 0x12345678.

- Little endian machine: Sure, an int is 4 bytes, but the first is smallest. I also read W X Y Z, but W belongs way in the back — it’s the littlest. The number is 0x78563412.

Same data, different results – not a good thing. Here’s an interactive example using the numbers above, feel free to plug in your own:

The NUXI Problem

Issues with byte order are sometimes called the NUXI problem: UNIX stored on a big-endian machine can show up as NUXI on a little-endian one.

Suppose we want to store 4 bytes (U, N, I and X) as two shorts: UN and IX. Each letter is a entire byte, like our WXYZ example above. To store the two shorts we would write:

short *s; // pointer to set shorts s = 0; // point to location 0 *s = UN; // store first short: U * 256 + N (fictional code) s = 2; // point to next location *s = IX; // store second short: I * 256 + X

This code is not specific to a machine. If we store “UN” on a machine and ask to read it back, it had better be “UN”! I don’t care about endian issues, if we store a value on one machine and read it back on the same machine, it must be the same value.

However, if we look at memory one byte at a time (using our char * trick), the order could vary. On a big endian machine we see:

Byte: U N I X Location: 0 1 2 3

Which make sense. U is the biggest byte in “UN” and is stored first. The same goes for IX: I is the biggest, and stored first.

On a little-endian machine we would see:

Byte: N U X I Location: 0 1 2 3

And this makes sense also. “N” is the littlest byte in “UN” and is stored first. Again, even though the bytes are stored “backwards” in memory, the little-endian machine knows it is little endian, and interprets them correctly when reading the values back. Also, note that we can specify hex numbers such as x = 0x1234 on any machine. Even a little-endian machine knows what you mean when you write 0x1234, and won’t force you to swap the values yourself (you specify the hex number to write, and it figures out the details and swaps the bytes in memory, under the covers. Tricky.).

This scenario is called the “NUXI” problem because byte sequence UNIX is interpreted as NUXI on the other type of machine. Again, this is only a problem if you exchange data — each machine is internally consistent.

Exchanging Data Between Endian Machines

Computers are connected – gone are the days when a machine only had to worry about reading its own data. Big and little-endian machines need to talk and get along. How do they do this?

Solution 1: Use a Common Format

The easiest approach is to agree to a common format for sending data over the network. The standard network order is actually big-endian, but some people get uppity that little-endian didn’t win… we’ll just call it “network order”.

To convert data to network order, machines call a function hton (host-to-network). On a big-endian machine this won’t actually do anything, but we won’t talk about that here (the little-endians might get mad).

But it is important to use hton before sending data, even if you are big-endian. Your program may be so popular it is compiled on different machines, and you want your code to be portable (don’t you?).

Similarly, there is a function ntoh (network to host) used to read data off the network. You need this to make sure you are correctly interpreting the network data into the host’s format. You need to know the type of data you are receiving to decode it properly, and the conversion functions are:

htons() - "Host to Network Short" htonl() - "Host to Network Long" ntohs() - "Network to Host Short" ntohl() - "Network to Host Long"

Remember that a single byte is a single byte, and order does not matter.

These functions are critical when doing low-level networking, such as verifying the checksums in IP packets. If you don’t understand endian issues correctly your life will be painful – take my word on this one. Use the translation functions, and know why they are needed.

Solution 2: Use a Byte Order Mark (BOM)

The other approach is to include a magic number, such as 0xFEFF, before every piece of data. If you read the magic number and it is 0xFEFF, it means the data is in the same format as your machine, and all is well.

If you read the magic number and it is 0xFFFE (it is backwards), it means the data was written in a format different from your own. You’ll have to translate it.

A few points to note. First, the number isn’t really magic, but programmers often use the term to describe the choice of an arbitrary number (the BOM could have been any sequence of different bytes). It’s called a byte-order mark because it indicates the byte order the data was stored in.

Second, the BOM adds overhead to all data that is transmitted. Even if you are only sending 2 bytes of data, you need to include a 2-byte BOM. Ouch!

Unicode uses a BOM when storing multi-byte data (some Unicode character encodings can have 2, 3 or even 4-bytes per character). XML avoids this mess by storing data in UTF-8 by default, which stores Unicode information one byte at a time. And why is this cool?

(Repeated for the 56th time) “Because endian issues don’t matter for single bytes”.

Right you are.

Again, other problems can arise with BOM. What if you forget to include the BOM? Do you assume the data was sent in the same format as your own? Do you read the data and see if it looks “backwards” (whatever that means) and try to translate it? What if regular data includes the BOM by coincidence? These situations are not fun.

Why Are There Endian Issues at All? Can’t We Just Get Along?

Ah, what a philosophical question.

Each byte-order system has its advantages. Little-endian machines let you read the lowest-byte first, without reading the others. You can check whether a number is odd or even (last bit is 0) very easily, which is cool if you’re into that kind of thing. Big-endian systems store data in memory the same way we humans think about data (left-to-right), which makes low-level debugging easier.

But why didn’t everyone just agree to one system? Why do certain computers have to try and be different?

Let me answer a question with a question: Why doesn’t everyone speak the same language? Why are some languages written left-to-right, and others right-to-left?

Sometimes communication systems develop independently, and later need to interact.

About Ambimat Electronics:

With design experience of close to 4 decades of excellence, world-class talent, and innovative breakthroughs, Ambimat Electronics is a single-stop solution enabler to Leading PSUs, private sector companies, and start-ups to deliver design capabilities and develop manufacturing capabilities in various industries and markets. AmbiIoT design services have helped develop Smartwatches, Smart homes, Medicals, Robotics, Retail, Pubs and brewery, Security.

Ambimat Electronics has come a long way to become one of India’s leading IoT(Internet of things) product designers and manufacturers today. We present below some of our solutions that can be implemented and parameterized according to specific business needs. AmbiPay, AmbiPower, AmbiCon, AmbiSecure, AmbiSense, AmbiAutomation.

To know more about us or what Ambimat does, we invite you to follow us on LinkedIn or visit our website.

References:-

https://betterexplained.com/articles/understanding-big-and-little-endian-byte-order/